The Never-ending Manifestations of Gambling in Children’s Spaces

As a teenager, I flirted with gambling and it teased me back. It came on strong and had no shortage of wingmen and enablers in its circle. I was sent over the edge on a chance encounter turned lifelong friendship.

The kind of gambling that snared us isn’t your run-of-the-mill mind-numbing slot machine where you chase matching symbols, or traditional card games like blackjack and baccarat–typical of casinos that take up physical space in the real world for real currency. No, this is a vice that only exists within the projection of pixels from our monitors and the gigabytes stored within our computers, in a computer game known as Counter-Strike.

“Green! Green! Green!” my friend would shout into his microphone as the roulette wheel spinned, as if his pleas-in-threes would ever so slightly increase his odds of winning. He was fiending for a digital currency that could be exchanged for in-game cosmetics on the online Counter-Strike themed casino CSGORoll. He would often livestream his degenerate gambling benders on Discord for a couple of our friends to watch, and I hate to admit that the uncomfortable dread of a man burning his last dollar and the shared excitement we felt when he won big was palpable–a microcosm of the gambling livestreams made popular by entertainers like Félix “xQc” Lengyel and Tyler “Trainwreckstv” Nignam.

Our small high school in Flushing, Queens did not have the bandwidth nor funding for any sports team, but Counter-Strike opened the door for us to explore a sense of competition that befit teenaged boys. We consistently broke night to just squeeze in one more game, first period algebra be damned. Our mantra, “Can’t get off on a loss,” likely cost us dozens of hours of sleep that we were better off having. As we continued to improve and climb the leaderboard, so did the monetary value of our opponents' cosmetics. Our exposure to these lucrative weapon skins made them increasingly desirable to us as a flex and a show of force. The idea of showing off hundreds of dollars in weapon skins was the equivalent to walking around Target fitted head to toe in Chrome Hearts when a “I paused my game to be here” t-shirt and some sweats would have been just fine—not to mention within our allowance budget.

To its detriment, the Counter-Strike skin marketplace has become bigger than the game itself. In the decade since we started to play, the digital skin market cap has reached over five billion dollars. This seemingly inconsequential digital skin marketplace is worth more than the entire GDP of Liberia and within the top 25 highest crypto currency market caps in the world. It’s not just a niche trend, it's a global economic reality. Skins, parading as vehicles of self expression, are exotic collectibles-turned investment assets for the likes of Neymar Jr., who has an in-game inventory worth more than $200,000. It would take a miracle, or perhaps the roulette enchanting spell of “Green! Green! Green!,” for someone of our economic circumstance to have a chance at a truly valuable skin.

Vanity eclipsed competition, and the frequency of our sessions continued to decline until the only time there was any interest in launching the game was when my friend lucked his way into a knife skin on CSGORoll. It didn’t help that, within an active game, players can open skin cases and have their findings broadcasted in the chatroom for everyone to see. Our competition and teammates became the advertisers and all of us were the targets. The publisher and developer behind Counter-Strike, Valve, created a money printer that runs like clockwork. Despite the damage it was doing to the game itself, to its players, to my friend, and to me, there was no incentive for them to stop or restrict it–no company in their right mind would pull the plug on a system that extracts over $1 billion per year from its player base. This amount of unchecked spending by its players moved Valve to make Counter-Strike entirely free to play in 2018, not because they are benevolent but because cosmetic item sales made the $15 entry fee obsolete.

Before we knew it, we no longer cared about being great Counter-Strike players, or finding meaningful community within that space. Our mantra became “Must get off on a loss.”

***

The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 1.2% of the world's adult population has a gambling disorder, with industry analysts anticipating that gambling revenue will reach over $800 billion by 2028. Their definition of gambling matches what Counter-Strike players experience when opening skin cases, “Risking money (or another item of value) on an event of uncertain outcome, with the possibility of gaining an increased return.” A key reasoning for the rapid normalization of gambling today is occurring through commercialization (skin cases) and digitization (digital weapon skins).

Counter-Strike is a quintessential manifestation of digitized gambling, but gambling had found its way to me long before I ever downloaded the game onto my computer. Whether it be a quarter spent at a gumball machine or a quarter spent on a temporary tattoo vending machine, gambling is inexorably woven into everything a child desires and the spaces they most frequently occupy. It is a vile practice that long preceded me.

In the late 1800s, tobacco manufacturers started to include collectible cards that depicted icons of popular culture within their packs of cigarettes. Bundling what would turn into the basis of a spending addiction with the world’s leading cause of cancer is a stroke of genius so profoundly evil that I have to refrain myself from applause—a prophetic gesture in turn-of-the century America. Though devilishly brilliant, this tactic didn’t take off for one simple reason: By 1939, every state had age restrictions for tobacco sales.

It wasn’t until 1951 that Topps took cues from the tobacco industry and solved their age problem. As it turns out, children love candy just as much as adults love tobacco, so Topps began to include collectible baseball trading cards with their iconic Bazooka bubble gum. Now unrestrained by minimum age laws, the card collector market was able to take off in proper form. Soon after, Topps turned this novel sales gimmick into a full scale card production operation. By 2021, Topps’ sports and entertainment business generated more than half of the company's revenue, and the next year Topps’ infamous 1952 Mickey Mantle card sold for a record breaking $12 million dollars at Heritage Auctions. That ridiculous figure is the result of a century-long capitalist psyop that convinced us that these pieces of paper have some sort of intrinsic value as cultural time pieces.

***

I was born in 1999, and this playbook has remained the same during my lifetime. As part of our daily routine, I harassed my father to take me to the Modells Sporting Goods on the ride back home from elementary school, but not because I wanted to buy Topps baseball cards that were all the rave when my father wore a younger man's clothes. What really captivated me were the Yu-Gi-Oh! card packs near the checkout registers.

Though I dressed up as Yugi Mutou for Halloween one year, and my favorite videogame before Counter-Strike entered my life was Yu-Gi-Oh! Forbidden Memories on the PlayStation 1 console, I never really cared about the rules of the card game. My prerogative was to show off all of the coolest looking cards in my collection to my classmates during our lunch hour and recess, such as the ultra rare Blue-Eyes White Dragon. The other kids stared in awe at how the sunlight reflected off of the card, illuminating its mesmerizing holographic tint.

To have sole ownership over this inconsequential piece of paper with artwork on it that my friends desired but couldn’t have. Yea, that felt good.

As much as it pains me that I had neither the foresight nor the understanding that the cards I was unpacking could be worth a significant amount of money one day (the aforementioned ultra rare Blue-Eyes White Dragon would sell for ~$70 today), there was no denying the high I felt from the short bursts of dopamine and instant gratification that came with opening Yu-Gi-Oh! card packs. Standard booster packs contain nine total cards, eight of which are common rarity. The final slot belongs to a rare, super rare, or ultra rare card. The frequency with which I was opening packs in pursuit of the awe I shared with my friends during recess was self-destructive and especially unkind to my father’s wallet.

Today, Yu-Gi-Oh! is one of the three most popular and profitable trading card games. I thought I had grown out of my childlike infatuation with Yu-Gi-Oh!, but the truth is, that feeling never escaped me. I am still chasing the gamblers high as an adult, just under the guise of the current gambling venture within spaces of popular culture, Magic: The Gathering.

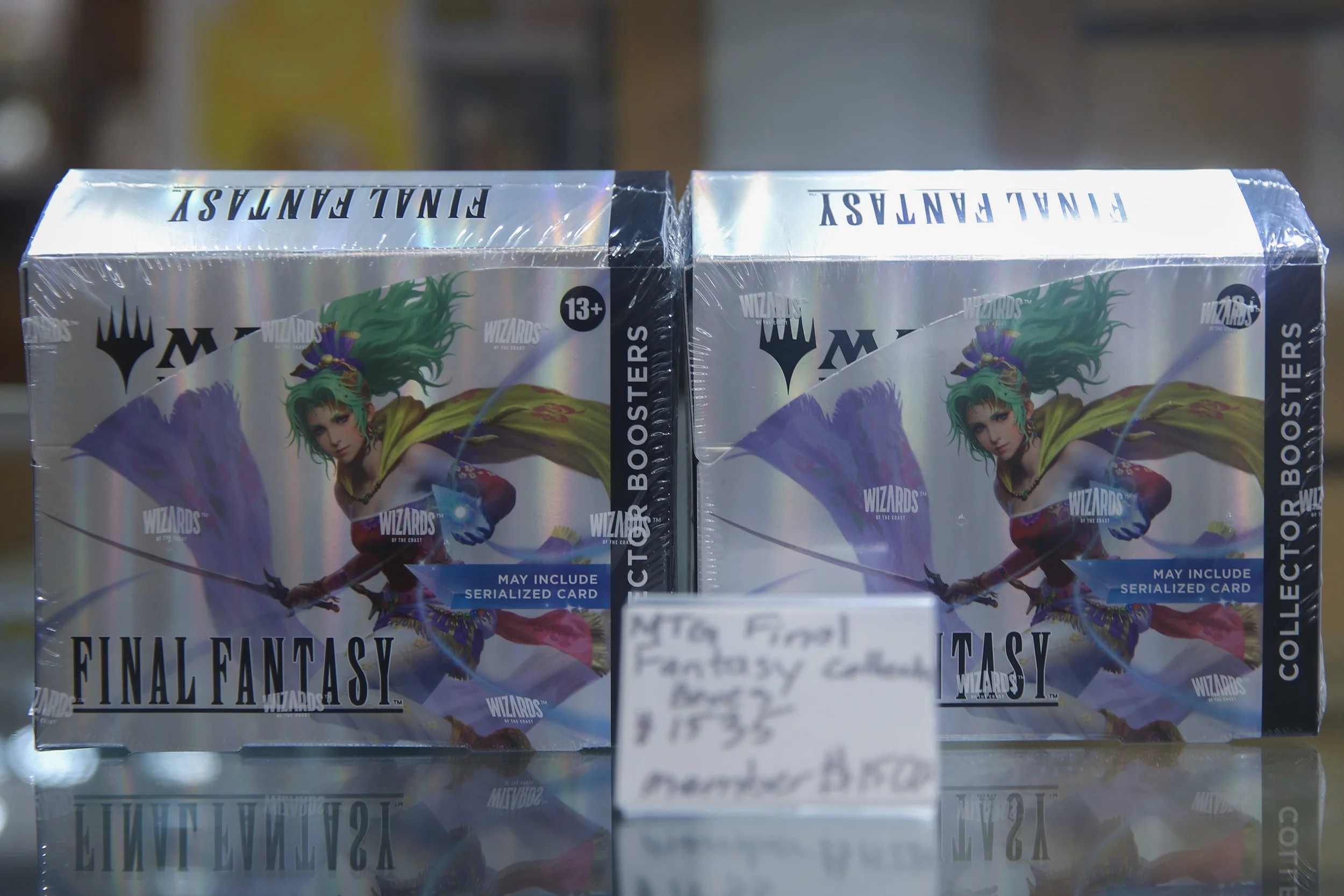

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, Wizards of the Coast, the toy company behind Magic: The Gathering, announced Universes Beyond, an initiative to introduce various nerd-adjacent franchises into their card game, among them Avatar: The Last Airbender,Spider-Man and Stranger Things. This is another stroke of genius that rivals the tobacco manufacturers from over a century ago— after all, a venn diagram of Lord of the Rings and Magic: The Gathering fans would be a perfect circle. The caveat is that licensing agreements are costly, so naturally that cost was passed onto the consumer, significantly hiking the price of booster packs and individual cards on secondary markets. Final Fantasy booster boxes cost $250, and the collectors editions go for over $1300. The consequences of the fandom premium for Universes Beyond cannot be understated. At first, these exciting collaborations existed in a bubble, and the cards were not allowed in official Magic: The Gathering tournaments. However, with the release of the Final Fantasy set, Wizards of the Coast announced that these premium collectors cards were tournament legal.

Hasbro had to quadruple their production to meet the high demand. “Lord of the Rings took six months to deliver $200,000,000 of revenue. Final Fantasy took one day,” the company’s CEO, Chris Cocks, said.

Jesse Robkin, a Magic: The Gathering competitor and vocal critic of Wizards of the Coast, fears for the direction of the game despite its record-setting profits. “I simply refuse to accept that the only metric for a game's health and success is sales,” Robkin writes. “I think that long-term stability and player retention, as well as overall quality of the game's health, both in casual and competitive spheres, is extremely important as well.”

Magic: The Gathering has gotten out of control, and it is impossible for players to keep up with all of the licensed card sets that are being pushed out. According to Robkin, “It's all premium these days. And there is no opting out.” She continues to explain that the only solution she can see is to lower the prices of standard Universes Beyond sets from $200-$250 to match their in-universe counterparts of $100-$150.

Unfortunately, as a lifelong fan of Final Fantasy games, my dormant childlike infatuation with trading card games was reignited. Just when I thought I was out, they pulled me back in. I felt gross spending over $500 dollars on booster card packs, commander decks, card sleeves, binders, and more. The entry fee to get started cemented a difficult truth: Universes Beyond is not a product for someone of my economic circumstance. New York City locals I spoke with at a weekly Magic: The Gathering tournament who have all committed a lot more time and money than I have shared a sentiment of acute buyer’s remorse when it comes to constructing their decks over the years, but they have an equally intense passion that makes it hard for them to let go.

An independent data study I conducted by scraping secondary markets for the pricing history of over 600 cards confirmed that there's never been a worse time to start investing time and money into Magic: The Gathering. Prices for standard set cards have increased by up to 600% since 2021, when Universes Beyond started to roll out. The price of cards from Universes Beyond sets like Final Fantasy are extremely frontloaded, and drop by roughly 50% over the course of 3-5 months. By the time those cards are somewhat affordable on secondary markets, the next set is already hitting the shelves of your local games stores. Rinse, repeat and watch your investment sink in real time.

***

In the same vein as Magic: The Gathering exists the latest gambling fad, Labubus. Those ugly-cute little monsters originated in a series of children's picture books, appropriately titled The Monsters, that Hong Kong artist Kaising Lung published in 2015. It wasn’t until a licensing deal with the Chinese company Pop Mart in 2019 that Kaising Lung’s creation outgrew its service to children. You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone with a Labubu keychain attached to their purse or schoolbag that recognizes them from The Monsters. The admiration for them comes from their manufactured exclusivity coupled with celebrity endorsements that range from the Korean popstar Lisa to future NBA hall-of-famer LeBron James.

Pop Mart’s signature money-makers are blind boxes. The less attractive and more accurate label for their flagship product would be “gamble boxes,” but that would be too problematic for something geared towards children. They are opaque packages that contain a “surprise” plush toy, keychain, or other collectible. The novelty is that you do not know what toy you'll get until you buy a box and open it. Of course, it wouldn’t be a good gamble without a grand prize, so each blind box has a 1/72 chance of containing an ultra rare secret collectible.

Yes, I was unhealthily obsessed with ultra rare Yu-Gi-Oh! cards, but even I was shocked by the extent that young adults have lost their minds over Labubus–something I bore witness to at the grand opening of a Pop Mart location at Flushing’s Tangram Mall. Over a hundred teenageers and young adults battled for a spot on a line twelve hours before the mall doors opened. It happened to be one of the coldest nights so far that year, but absolutely nothing was going to get between their hard-earned money and the opportunity to spend it on Labubus. Hell broke loose when Tangram Mall officials fired the starting pistol to line up. Adults shoved teenagers to the ground, people shouted at each other while they jockeyed for position, and some even complained to mall security over foul play. The local authorities that were tipped off ahead of time eventually intervened to force the crowd of Labubu-craving maniacs into a line. The levels of hysteria evoked Black Friday shopping before Amazon graced us with same-day delivery. By the time some semblance of sanity was reached, a passerby asked me, “What are they all lined up for?” I told him, “Plush toys.” He laughed.

Beyond Labubus, Pop Mart secured licensing agreements to produce gamble boxes for some of the most recognizable individual properties in the world: Mickey Mouse, Hello Kitty, The Powerpuff Girls, Snoopy, and even One Piece. It has never been more frustrating for parents to get trendy toys for their children during the holiday season. At least families that cannot foot the bill for extravagant Labubus have access to a thriving market of counterfeit gamble boxes and knock-off products that are marked down significantly. Street vendors, gas stations and bodegas shamelessly sell dupes of Pop Mart’s gambling boxes, which is as good of an indicator as any that this kind of predatory product has reached a normative status in record time.

***

There is no sugarcoating how dangerous it is that gambling has become a primary way for children to engage with their favorite sources of art, popular culture and entertainment. Tobacco, bubble gum, Counter-Strike, card games and Labubus all push the boundaries of acceptability for gambling, and they all lead to the same destination: Empty pockets and intense regret. The roulette wheel continues to spin–the cyclic dopamine rush of short term gratification in exchange for long term economic damage will be embedded in their psyche. The same children who grew up in an environment of speculative economic exploitation are now betting on our very democratic processes with prediction based markets like Polymarket.

Needless to say, children’s gambling enables adult gambling. If we are comfortable enough to allow our children to participate in it, we are well beyond the point of establishing boundaries to address its pervasiveness. Kalshi, a federally regulated U.S. exchange, allows users to “trade event contracts” on election, sports, economics, politics, and even cultural outcomes. You can now legally wager money on Gavin Newsom becoming the 2028 democratic nominee for president; on Marty Supreme winning best picture at the Oscars; on how many inches of snow New York City will get this month. Kalshi just announced a data integration partnership with CNN, “as a powerful complement to CNN’s reporting,” This partnership will bring real-time prediction markets to every television screen in America as a “credible” source of information, as if what people are believing will happen in the future is as valuable in a newsroom as our lived present reality. It does not end there–the very neighborhood I grew up in, Flushing, will become unrecognizable now that the New York State gaming commission approved billionaire Steve Cohen’s casino bid, enabling his plan to transform Citi Field into a “sports and entertainment complex.” The grim future forecasted by the proliferation of gambling in children's culture will continue unless we make a sharp turn in the opposite direction.

Disrupting that trajectory starts at home, within the very communities gambling seeks to extract as much money as possible from. Magic: The Gathering players have already taken initiative to protest the exuberant costs of cards by printing counterfeit cards themselves rather than directly purchasing them from Wizards of the Coast. This is known as proxying. Resources and tutorials on how to print proxy cards are easily accessible on YouTube and Reddit, which double as forums where community members speak candidly about their frustration with the state of the game, but also the satisfaction of being able to enjoy it again without a price barrier. YouTube user Verd24 commented on a proxy tutorial, “With the direction Magic is going, I've decided to finally jump into proxies and sell a good chunk of my collection. I love the game, but I have no desire to be so financially invested in it anymore.”

Wizards of the Coast’s policy on proxy cards is that only authentic Magic cards are allowed at sanctioned events. Players can be disqualified and banned for using proxy cards in their decks, and any individual or retailer that deals in counterfeits could face legal repercussions. According to a 2016 press release from Wizards of the Coast, “We will continue to work quickly and decisively with law enforcement agencies around the globe to protect against the creation or distribution of counterfeit Magic cards.” Despite this, there is a gentlemen's agreement between players not to report usage of proxy cards within sanctioned tournaments, and some local Magic tournaments do not bother enforcing proxy rules. During a Yu-Gi-Oh! tournament at Montasy Comics NYC, I noticed that players were even using proxy cards with custom artwork, some commissioned and others pulled off the internet. These players found a way to creatively express themselves in response to a grim economic reality looming over their favorite hobby. Sure, it's bleak that a tournament legal competitive Yu-Gi-Oh! or Magic deck can cost upwards of $1000, but there exists a space for players to counter systems that threaten their tightly knit communities. This is even true of Labubu fanatics, where large group chats on Instagram and Whatsapp have become hubs to trade plush toys one-for-one if they are disappointed by the toy they got from their gamble box.

While not ideal, these bandaid solutions are a step in the right direction. We aren't just aimlessly sprinting towards a future where there's a casino built in every major city, democratic elections and culture awards shows are subject to prediction markets, and every toy has an underlying random-chance outcome. As long as there is a community built in protest against these broken predatory systems, there will be no need to gamble as if our lives depended on it.